To Don Ludwig, it feels like déjà vu.

His yard backs up to the megasite in Mundy Township, where his wife Dawn’s grandparents built their house along a tract of farmland near Flint in 1965.

For the past two years, economic developers have been quietly assembling acreage for what could be a $55 billion microchip factory. It’s giving Ludwig flashbacks.

When he was 12 years old and living with his grandparents in Detroit’s Poletown, they were forced from their home through eminent domain to make way for a General Motors assembly plant. Around 1,500 homes were seized and the neighborhood leveled.

While the law wouldn’t allow that to happen by force today, Ludwig knows the end game is clearing a path for the Advanced Manufacturing District of Genesee County — a once-in-a-lifetime economic opportunity, as proponents present it.

“Eventually, I know they’re going to come for me,” Don Ludwig said, standing next to a “no megasite” sign on his front lawn, which he believes is being targeted as an access point for the industrial complex. “Everybody can be bought out, but I’m gonna fight it to the end for the people who are not fighting it.”

Residents in Eagle Township near Lansing thwarted a similar attempt to develop a megasite, citing many of the same concerns. When local support for that project collapsed, all of the state’s efforts turned toward Mundy.

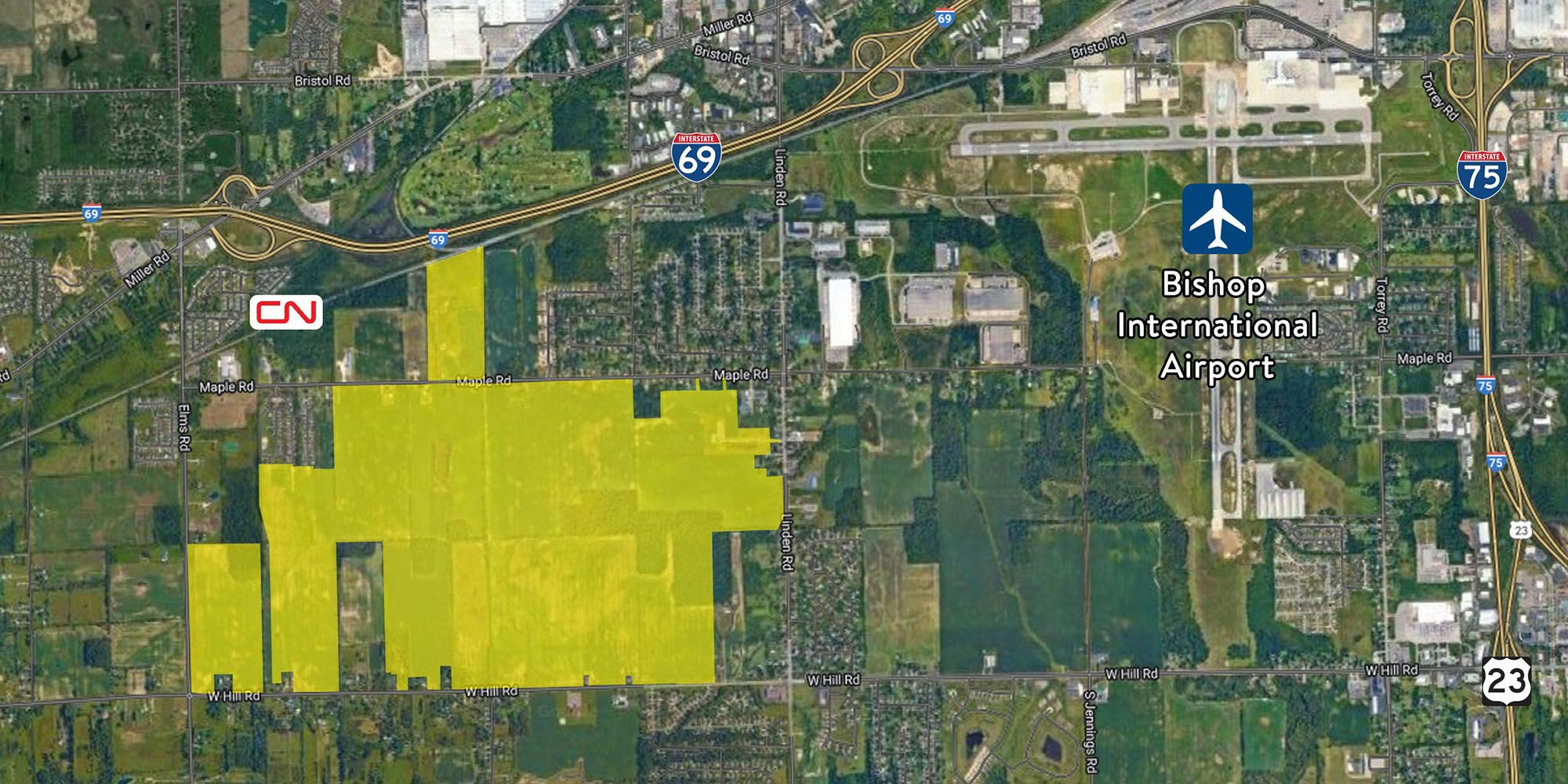

Activity has picked up at the site near the I-69/I-75 juncture. It is in the mix for a mammoth 10,000-jobs microchip manufacturing development, code-named “Project Grit,” by San Jose-based Western Digital Technologies Inc., sources told Crain’s.

Land clearing is expected to start in the coming weeks after economic developers used a $250 million grant, approved in May, to buy and take control of more than 1,000 acres. Developers are looking to put under contract more acreage but say they have what they need for a large project.

A spokesperson for the Flint and Genesee Economic Alliance, which is heading up megasite development efforts, said no one is being forced from their homes and that several property owners have been approached with “more than fair offers that factor in the magnitude of this project and circumstances.”

The microchip project hinges on billions of dollars of funding from the federal CHIPS and Science Act. The U.S. Department of Commerce has so far announced $35 billion in proposed direct funding for semiconductor investments around the U.S. and plans to allocate all $39 billion by the end of the year.

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer said Michigan is “well positioned” to win a large semiconductor fabrication plant, and she is optimistic about landing one.

“We’ve gotten a lot of great investment in a variety of parts in our economy, but so much of what we produce here relies on chips,” Whitmer told Crain’s last week on the sidelines of The Battery Show in Detroit. “We’ve got the unique expertise, access to water, workforce. I mean, we’ve got a powerful story to tell. We’ve been in the mix on a number of opportunities. We’re going to continue to put our best foot forward.”

The governor said she couldn’t provide a date for when a funding decision will be made.

“I have found it’s never a good idea to predict when the federal government is going to act,” she said. “Hopeful that we’ll have some news soon, but I don’t have a firm date from the feds.”

Supporters call the Mundy megasite a potential lifechanging economic opportunity for a region that has suffered greatly from job and population loss. If Project Grit were to materialize, it would likely be the largest economic development project in state history, a “game changer” for Flint and “vindication” for all it has been through, as one local business owner described it.

The Ludwigs and others in its path see things differently.

“We’re not against it. Just put it somewhere not in the middle of subdivisions,” Ludwig said. “I’m fighting just to keep everybody’s water safe. That’s the biggest thing.”

Pollution, depletion of water resources and a seismic disruption to life in the quiet Flint suburb are some of the top concerns of a dozen or so residents near the megasite who spoke with Crain’s. So, too, are bold job claims and promises that many believe will never be met.

It’s impossible to know how valid those concerns might be, but perhaps the biggest issue is that many residents feel left in the dark. Non-disclosure agreements abound, from local and state officials to economic developers. Some farmers and landowners also stopped talking to neighbors after executing purchase options and signing NDAs, creating a divide in the small community, according to some residents.

“We have no confidence or trust in our township or officials,” said Steven Phillips, who has lived across the street from the megasite boundary for 30 years. “They basically turned their back on thousands of people, hundreds of homes.”

From the Ford-CATL battery plant in Marshall to a Chinese battery factory near Big Rapids, large-scale development projects have been met with fierce resistance and NIMBY-ism (“not in my backyard”) by Michigan residents directly impacted. The long-term benefits of those projects reach far beyond their footprint and outweigh the negatives, state officials and economic developers argue.

But the distrust of government and industry runs especially deep around Flint, a city that’s been defined by the exodus of GM and automotive jobs — and, more recently, the water crisis. Ten years ago, in October 2014, GM announced it would stop using Flint River water at its engine plant because it was too corrosive for vehicle manufacturing, but state and local officials promised it was safe to drink.

While the impacts of the water crisis still linger in the city of Flint, Mayor Sheldon Neeley said his community is on the rebound. From the redevelopment of the former GM Buick City site — where a $60 million battery plant is being developed — to the Mundy Township megasite, Neeley said Flint is ready to land “transformational” projects and restore its manufacturing might.

“Remember, we are the birthplace of a billion-dollar corporation,” Neeley said. “At one time, Flint was home to a quarter-million people. Our infrastructure is built for this type of thing.”

While the opposition is strong on the periphery of the megasite, where protest signs like the Ludwigs’ have sprouted up on front lawns, further from the footprint others see the magnitude of the opportunity.

“In my lifetime, this will be the largest most significant project in this area, and probably my three kids’ lifetimes,” said Matt Cramer, third-generation co-owner of Grand Blanc-based Dee Cramer sheet metal contracting company.

The project represents a huge business opportunity for the company, which did the ductwork for GM’s Ultium battery plant in Delta Township outside Lansing and several others around the country. Besides the boost to skilled trades in the region, landing such a large project could be “a real vindication” of all Flint has been through, Cramer said.

Bernard Drew agrees. He and his wife Christel run a property redevelopment company in the city of Flint, giving them a direct line of sight into its hardships and potential. Projects like Buick City and the Mundy megasite have injected a lot of optimism into the community, Drew said.

“Just the sheer prospect that those type of developments are coming to the area, I think it’s extraordinary,” he said.

Given Flint’s history, however, all the promises should be met with some skepticism and there should be a plan to ensure everyone benefits, Drew added.

“There are some underlying levels of distrust, some earned justifiably,” he said. “I think it’s important that there needs to be steady, authentic communication about what’s taking place. There should be advanced planning for the pathway for some of these smaller businesses that will support this injection of new jobs.”

Local Realtor Kristy Cantleberry said development of the megasite is inevitable, so residents might as well embrace the bright side.

“With change and development, you’re always going to have pros and cons,” she said. “Growth, in my opinion, is a great thing.”

The business owners share an obvious interest in that they stand to benefit directly from the economic development. They also have something else in common: The desire to see their kids stay in Genesee County.

“It’s going to create more jobs, and probably high-level jobs, for the young people in this community,” Cantleberry said. “It’s going to create more housing and excitement. We need that. We desperately need that.”

Tyler Rossmaessler, executive director of the Flint and Genesee Economic Alliance who is heading up development efforts at the Mundy megasite, said the projects have more to do with the future generation.

“What I’m most excited about, as someone who’s raising a family here, is the opportunity that projects like this represent for young people,” he said during a media event for NanoGraf’s planned Buick City project. “Projects like this, with cutting edge technologies, legitimize Flint as a place to do business and will spur more investment.”

In 2021, a challenge from billionaire real estate mogul Stephen Ross set things in motion.

Ridgway White, president and CEO of the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, wanted to bring a megasite to Flint. Developing shovel-ready sites had become a top priority in Michigan after Ford Motor Co. announced it would invest $11.4 billion for new factories in Tennessee and Kentucky, rather than its home state.

Coming out of the Flint water crisis, White made it his foundation’s mission to spur economic development and job growth in the region.

“We realized that the No. 1 things that were the most important for residents of Flint and Genesee County was figuring out how you create jobs and how you have quality schools,” White said.

But the nonprofit executive couldn’t find a contiguous piece of land that could accommodate a massive development. He voiced those struggles to Ross when the real estate giant was in Flint for a University of Michigan board of regents meeting to discuss the UM Center for Innovation in Detroit.

“I got to talking to him about the megasite and said, ‘We can’t find a thousand acres, it’s really hard,’” White recalled. “He said, ‘If I can put together Hudson Yards, you can find a thousand acres in Southeast Michigan.’”

That weekend, as White and his family were driving around in search of reclaimed barn wood for the fireplace mantle of his new house, he passed a large stretch of land.

“I looked over and said, ‘That’s a lot of land,’ and pulled my car over and pulled up Google Earth and said, ‘Wow, there’s seven people on about 900 acres …”

White shared his findings with the Flint and Genesee Economic Alliance, and the regional economic development group, along with its Detroit Regional Partnership counterpart, ran with it.

Ludwig, one of the residents in the project’s path, said he has been ignoring calls from a Cooper Commercial representative wanting to talk about property acquisition. He’d rather ride it out as long as he can, and if the development really is inevitable, maybe there’s a pot of gold waiting for him at the end.

“I’ve been told an open checkbook is coming our way,” he said.

Julie Asselin, who lives up the block from the Ludwigs, has about 10 acres of farmland that she said is within the targeted megasite. She and her husband David, a retired GM worker, have lived in their home almost 40 years. She’s not been approached about the property, nor does she want to be. She wishes the developers would go somewhere else for the project.

“They probably want to take it,” she said of her land. “I like where I’m at. We got a good neighbor next to us, and they’re really nice people.”

Owning a home is a keystone of wealth… both financial affluence and emotional security.

Suze Orman