The juice

In this case, the juice is economic investment in low-income areas that have seen disinvestment.

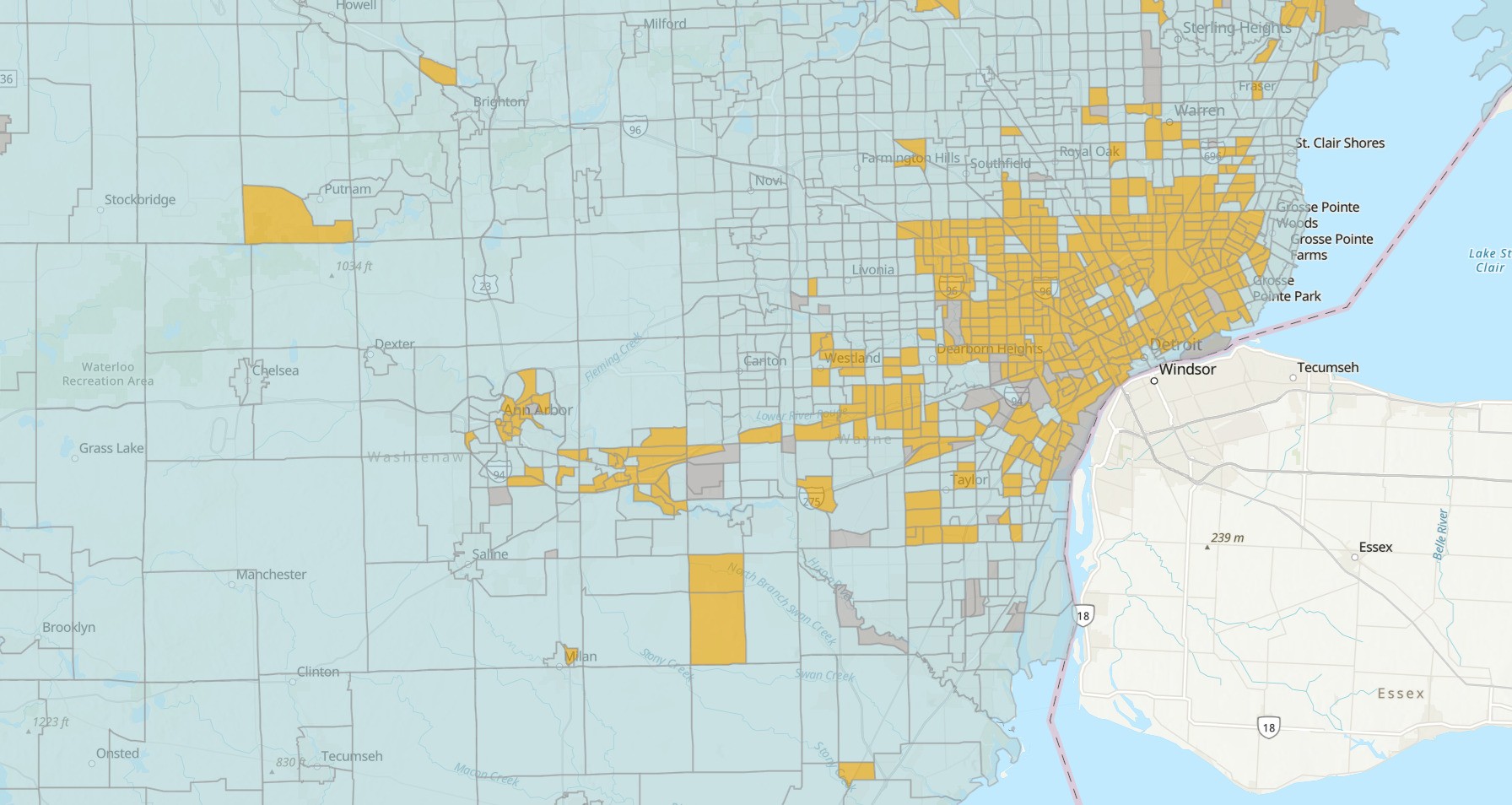

To get to it, you have to squeeze through a complicated combination of rind and fruit that involves governors designating certain areas as Qualified Opportunity Zones based on median family income and poverty rates and establishing a graduated capital gains tax deferral granted by placing those investor gains into special funds to invest in those areas through things like commercial real estate and business development.

There are different regulations for metropolitan QOZs vs. a new classification called Rural Qualified Opportunity Zones, or RQOZs, which get beefier tax benefits for investors. Governors are also required to designate RQOZs as one-third of the Opportunity Zones they designate, a new rule under the One Big, Beautiful Bill Act.

The new law also adds reporting requirements that have long been demanded.

The U.S. Department of Treasury, under the OBBBA, will be required to create annual reports on the number of QOFs and their assets, according to the EIG. Other required data includes the number of designated QOZs and RQOZs and their confirmed investments, plus information on investment sectors, housing units created and employment impacts, the EIG says.

In addition, other more long-term reporting requirements include measuring the “socioeconomic performance” of QOZs vs. comparable non-QOZs based on things like job creation, poverty rates, income, housing and business formation, according to the EIG.