A Michigan tax incentive program that has been crucial for massive urban infill developments across the state is running out of money.

Funding for the Transformational Brownfield Plan program is nearing a $1.8 billion cap and would need legislative action in Lansing to expand, as it was in 2023.

Some developers are already sitting on the sidelines with projects, including a $1.6 billion plan to partially demolish and redevelop the Renaissance Center in Detroit, that can’t happen until the program is re-upped.

“In terms of the TBP program, we have clients with invitations to apply under the existing cap space, and clients who are also on the sidelines hopeful that the Legislature will increase the cap,” said Joe Agostinelli, founder of Michigan Growth Advisors, a subsidiary of Grand Rapids-based law firm Miller Johnson. “Hopefully the Legislature raises the cap. That would be the best outcome.”

Agostinelli, who previously held posts at the Michigan Economic Development Corp. and Kalamazoo-based economic development organization Southwest Michigan First, is ushering a $797 million riverfront project in downtown Grand Rapids through the incentives process. Fulton & Market, a project proposed on land owned by the DeVos and Van Andel families that calls for three high-rises with office, residential and a hotel, is angling for nearly $320 million in tax increment financing under the Transformational Brownfield program.

Fulton & Market is one of five projects that is “under invitation to apply,” which means the funds are earmarked in the program even though the transformational brownfield plan still needs approval from the Michigan Strategic Fund board, which oversees the MEDC.

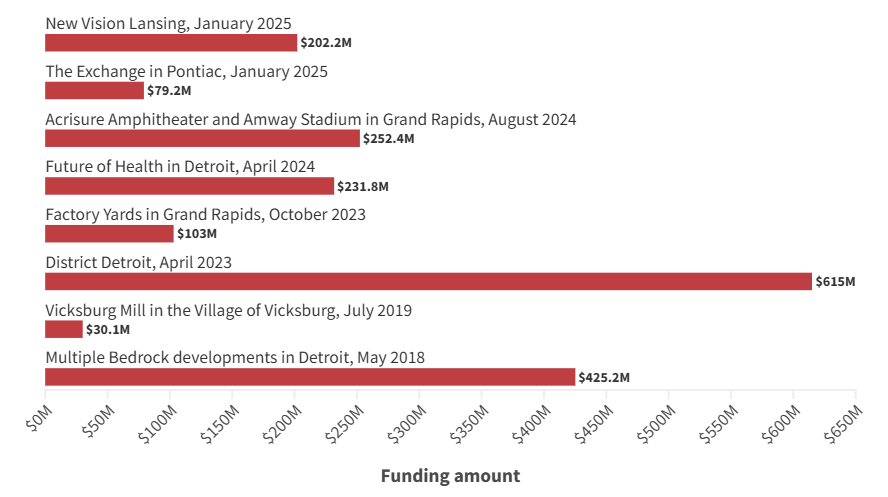

Eight Michigan projects have received Transformation Brownfield incentives since the program was established in 2017.

Agostinelli says the remaining funds in the program are likely only enough to back one smaller-sized project.

Officials with Dan Gilbert’s Bedrock LLC say the cap should be expanded not only to facilitate the company’s redevelopment of the Renaissance Center, but also projects in Grand Rapids, Sterling Heights, Dearborn, Muskegon and Traverse City.

Communities “need this program to live on,” Jared Fleisher, vice president of Gilbert’s Rock Family of Companies, told Crain’s Grand Rapids Business.

“Since all the available program authority has been committed, the MEDC is not able to take new applications,” Fleisher said in an email. “In addition to the Renaissance Center, there are transformational redevelopment projects across the state that need the TBP program to be extended to make it possible for them to move forward.”

In addition to helping repurpose challenged urban properties, Fleisher said the program is “completely fiscally responsible and performance-based.” Bedrock intends to make those arguments with lawmakers.

“The new legislature is just getting organized,” Fleisher said. “In the coming months, we intend to work with stakeholders from across the state to make the case for continuing the TBP program and explain what it means for communities across Michigan.”

Fleisher noted that the tool has had bipartisan support since it was enacted in 2017, and in July 2023, when Gov. Gretchen Whitmer signed bills to double the caps in the program and expand the tool to more qualifying projects.

While officials with Bedrock — which is working with General Motors to move the automaker’s longtime headquarters from the Renaissance Center to Bedrock’s Hudson’s Detroit building — have said public subsidies would not be used to partially demolish the multi-tower RenCen, incentives would support public infrastructure, public spaces and the redevelopment of obsolete buildings there.

“Bedrock and General Motors are solely focused on working with stakeholders from across the state to explain the value of the TBP program — how it is a proven, fiscally responsible program that is truly working to make transformational projects possible across the state,” Fleisher said.

State Rep. Alabas Farhat, D-Dearborn, introduced legislation in November 2024 to raise the annual cap for the transformational brownfield program, which subsidizes projects by letting developers keep increases in various taxes for two decades. The bill died without a hearing during the lame-duck session. Legislation would have to be reintroduced to be considered in the 2025-2026 term.

“Communities across our state right now are waiting to get their projects moving because of the fact that the brownfield program right now has reached its limit,” Farhat said.

The brownfield incentives program, he said, “is a smart, fiscally responsible approach to revitalization — turning blighted buildings into vibrant spaces, safeguarding our environment and spurring economic growth. Developers don’t see a dollar of incentives until after the project is completed and they meet locally set requirements.”

The transformational brownfield program allows developers to capture a portion of incremental taxes generated from five sources: construction income tax, property tax, income tax, withholding tax, as well as sales and use tax.

The MEDC tracks how much of the program’s $1.8 billion financing cap has been spent since the program started in 2017. As of Jan. 31, $116.8 million remains in the program’s $200 million construction-period tax capture bucket, while just under $10.9 million is left for the $1.6 billion post-construction income, withholding and sales/use tax capture. The post-construction taxes are captured for 20 years.

Projects that have made it far enough in the due diligence process of a transformational brownfield plan fall under “under invitation to apply.” If they don’t receive the final approval, those incentive amounts would be returned to the pot of available financing for other developers. The Michigan Strategic Fund board has approved every transformational brownfield plan it has considered.

“There is definitely a need for more incentives, for the cap to increase,” Agostinelli said. “I think the reason the cap keeps getting consumed both times the legislature increased it is because this incentive program works for large projects.”

Projects that apply for the program are complex, and require “rigorous due diligence efforts to ensure the viability of the project,” said MEDC Chief Place Officer Michele Wildman.

Once a project is “under invitation to apply,” the developer has 90 days to submit a final application, and four to six months to proceed to the MSF board for consideration, Wildman said.

“The TBP program is an incredibly helpful tool for developers because it provides financial incentives and support for redeveloping underutilized sites that will result in a revitalized asset for the community,” Wildman said via email.

The $797 million riverfront Fulton & Market project in Grand Rapids is especially expensive because the land used to be part of the Grand River, but was later filled with low-quality aggregate. The site now needs geotechnical reinforcement to support the three towers that would be built as part of the project.

The Fulton & Market development team has said the project would not be financially feasible without the transformational brownfield tool. If the program does not receive additional funds, future projects that would have applied for the program will get shelved, Agostinelli said.

Jared Belka, partner at Warner Norcross + Judd LLP, worked with the development teams behind Grand Rapids’ two projects that received transformational brownfield incentives: Grand Action 2.0’s Acrisure Amphitheater and Amway Stadium, as well as the $147 million mixed-use Factory Yards project.

He is also working with Parkland Properties as it seeks transformational brownfield financing to redevelop the former Shaw Walker Furniture Co. building near Muskegon Lake.

“There is no other tool that can backfill this, and if you want to continue to see impactful projects in communities, and many of these are sites that you walk or drive by on a daily basis, those projects are not going to move forward without some level of significant support,” Belka said. “The right projects that are able to utilize this, it’s a game changer and it would be tough to see if it’s not expanded.”

The Shaw Walker transformational brownfield incentives are earmarked as “under invitation to apply,” but the developer still hopes to see the tool expanded.

“(The TBP) is important because construction costs and interest costs are so much higher than they used to be and the rental rates have not kept up,” said Jon Rooks, Parkland Properties president and owner. “Interest rates have almost doubled and construction costs are up almost 50% over the last five years, and the rental rates of apartments have not climbed as much.”

The Shaw Walker project would not have penciled without the transformational brownfield program, Rooks said.

“Shaw Walker is a generational project, it’s transformational and it’s important to the city of Muskegon and all of West Michigan, partly because of the housing crisis and partly because of the blight it fixes,” Rooks said.

Parkland Properties also proposes to redevelop the contaminated former Sappi paper mill site along Muskegon Lake’s south shore. Environmental cleanup of the site will be a massive undertaking. Parkland is still early in the planning process and working to get approval from state regulators to develop the property, said Rory Charron, chief operating officer at Parkland Properties.

“(The TBP program) is definitely one avenue we’ve considered,” Charron said of the paper mill project. “That is also just a massive, large legacy project, and you get into the same boat as we do with Shaw Walker. It’s definitely an option, but obviously the program has caps on the funding availability.”

Crain’s Detroit Business reporter David Eggert contributed to this report.

Owning a home is a keystone of wealth… both financial affluence and emotional security.

Suze Orman