Credit: Screenshot

A view looking north from Big Beaver Road of the conceptual rendering of the proposed Somerset West project in Troy on the former Kmart Corp. headquarters site.

A prominent metro Detroit developer and landlord expressed an unusual level of anger publicly Tuesday evening during a Troy Planning Commission meeting in which that body asked for several additional items before it would consider recommending approval to the Troy City Council.

Nathan Forbes, who runs Southfield-based Forbes Co., has been pitching a new vision for the former Kmart Corp. headquarters site at West Big Beaver Road and Coolidge Highway, first publicly talking about the new vision back in September before the commission.

It would be anchored by a new $250 million University of Michigan multi-specialty, ambulatory care facility, plus include other uses.

And when the nine-member commission voted on Tuesday evening following nearly three hours of discussion to hold off on recommending approval of a planned unit development conceptual plan, Forbes’ frustration appeared to boil over.

“Shame on us, and shame on everybody in this room,” Forbes said to the commissioners, one of whom was absent from the meeting. “We have spent seven months keeping this deal together and trying to codify this deal. If I had known for one minute that the University of Michigan should have been here presenting their design, and their development and their plans, they would have been here.”

One major bone of contention the commission had during Tuesday’s meeting was the university, as what city officials described as a “body corporate” under state law, is not required to abide by local zoning codes, not to mention other local regulations.

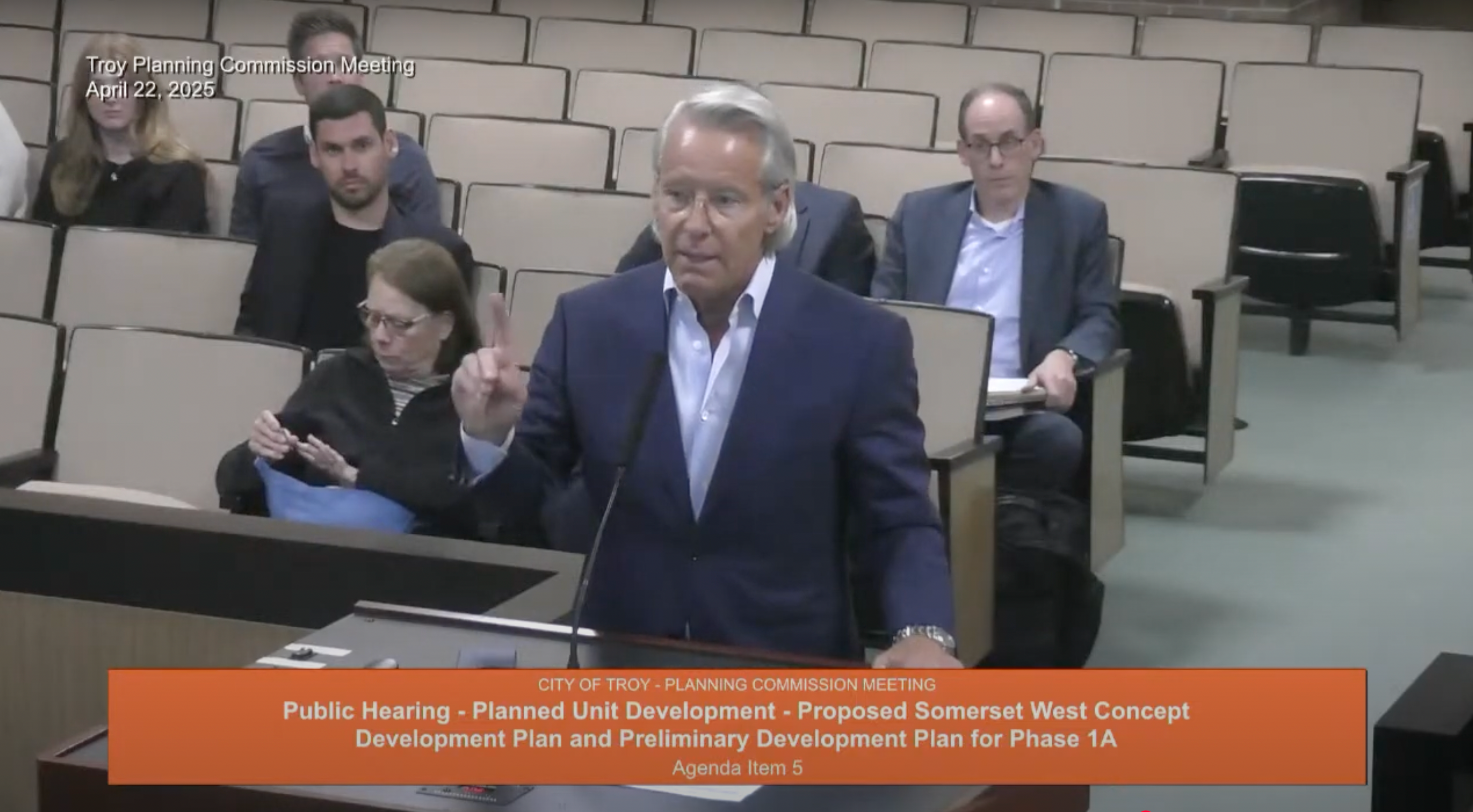

Credit: Screenshot

Nathan Forbes, head of Southfield-based Forbes Co., addresses members of the Troy Planning Commission following their 7-1 vote to postpone a decision on the future of the former Kmart Corp. headquarters property.

After the commission’s 7-1 vote to postpone a decision pending various considerations and requests, Forbes returned to the lectern to fire back.

“We could sell the whole 28, 40 acres to UM today and the city would have nothing to say about it. That’s not my intent,” he noted after inquiring about whether a previous planned-unit development for the site had expired, allowing him to unload the property if he so chose.

“I am not sure what we have been talking about in this PUD plan for seven months, but I’m a little bit fit to be tied,” Forbes continued. “I’ve spent hundreds and hundreds of thousands of dollars with my attorneys and my planners and traffic consultants going through all this iteration to get from where we were to in front of you last time, (when) we had two or three comments we were supposed to address, and now we have 30 comments we are supposed to go back and address. So I’m not quite sure what this collective group has been doing for seven months. If you call that frustration, it is.”

As Forbes was stepping away from the microphone, he returned with a parting comment: “And maybe we’ll see you again, and maybe we won’t.”

After his remarks, Forbes left the meeting room, followed by what appeared to be several members of his team.

The commission then proceeded to take a five-minute break.

Among the commission’s requests: Having the university present a master plan for the 17 or so acres it controls, which includes five acres north of Cunningham Drive, plus 12 acres south of it where the new medical facility would go. The commission also requested that it be provided the minimum — not just the maximum — amount of housing, office, retail and other space that would be incorporated into Forbes’ Somerset West project, on the other side of Coolidge from his and the Frankel family’s Somerset Collection luxury shopping center.

It also wanted Forbes to consider increasing the size of allotted park space from a little over one acre, and restrict the types of uses that could go on the site by excluding things like auto-focused businesses, trade schools, appliance sales, and certain types of residential, including townhomes, single-family housing and nursing facilities.

Through a spokesperson, Forbes declined further comment on Wednesday.

Luke Bonner, a development advisor who is CEO of Ann Arbor-based consultancy Bonner Advisory Group and also economic development advisor to the city of Sterling Heights, said there seems to have been a communication breakdown between the city and Forbes leading up to Tuesday’s meeting.

“For projects of this size and importance, both sides need to be very well organized and transparent with one another,” Bonner said.

Brian Connolly, a University of Michigan land use professor who is a former commercial real estate attorney, said frustration can run high in meetings like those.

“As someone who has spent hours in evening hearings on development projects like this, it is sometimes hard to contain your frustration,” Connolly said. “I have been there. It takes a lot to maintain your composure, particularly if you’re somebody who’s got a lot of money on the line and you’ve spent a lot of time and money working on something. I understand that emotion.”

The commission also expressed concerns about what would happen north of the proposed University of Michigan facility. In the original vision dating back to September, there would have been a parking deck immediately to the north of it. However, in the revised plans shown last night, the deck had been eliminated in favor of about six acres of surface parking instead.

That, Forbes said, was to allow for what he said was the almost certain need that UM will have for future expansion of the facility. A parking deck in the originally proposed location would limit the ability for the university to do that. Once the anticipated UM facility expansion takes place on the land where the parking deck was originally slated to go, two parking decks flanking the expansion would be constructed.

“This is their facility for all of Oakland County,” Forbes said. “They know on Day No. 1 they are undersized. This is what’s been approved by the regents and Michigan Medicine. My intuition is that it won’t be long before we are back in front of you for a natural expansion of this building.”

R. Brent Savidant, Troy’s community development director, said Wednesday that Forbes needs to submit a revised concept development plan addressing the Planning Commission’s requests. There has not been a future meeting date set to consider any revisions.

It would ultimately be up to the Troy City Council to sign off on the planned unit development and the concept development plan, Savidant said.

The long-vacant former Kmart property is owned by a joint venture between the Forbes and Frankel families.

In March 2024, UM revealed its medical center plans for the site, which is about 40 acres. Last month, the university said it needed more land for the project. Approximately 12 acres north of Cunningham Drive are subject to a consent decree, and the development vision put forward is primarily for the 28 acres to the south.

In addition to the medical facility, the development could include up to 750 residential units, up to 500,000 square feet of office space, up to 300,000 square feet of retail and a hotel with up to 250 rooms and parking.

The former Kmart headquarters had long been vacant when demolition on the hulking, 1.1-million-square-foot former office complex began in the fall 2023.

After Kmart vacated it in the mid-2000s and moved to Illinois as a subsidiary of Sears Holding Corp., it continued its well-documented implosion across state lines.

Sidney Forbes, founder of Forbes Co., told Crain’s in 2012 that the purchase of the Kmart property “was a defensive move” after Farmington Hills-based Grand/Sakwa Development began courting Somerset Collection tenants for a retail development.

“So when we had the opportunity to buy that land, we took it,” Sidney Forbes said in 2012. Grand/Sakwa’s plans stalled at the Troy City Council and there has been little action on it since.

At its peak, the Kmart property accommodated 5,000 employees. When it was sold in 2005, it had fewer than 1,900, many of whom were transferred to Illinois.

Kmart’s last store in Michigan closed in November 2021, ending its run of nearly six decades after its first store opened in 1962 in Garden City. Financial woes hampered the retailer during the last two decades; it sought bankruptcy protection in 2002-2003 and eventually merged with Sears, Roebuck & Co. in 2004.

Owning a home is a keystone of wealth… both financial affluence and emotional security.

Suze Orman